Andrew LaMar Hopkins

Andrew LaMar Hopkins (b. 1977, Mobile, AL) Andrew LaMar Hopkins is a singular voice in contemporary American painting, renowned for his meticulously detailed depictions of 18th- and 19th-century Southern interiors, architecture, and daily life. Deeply rooted in historical research, his work reconstructs the largely erased histories of Free Creoles of color, particularly in New Orleans, where he had lived for decades. Hopkins also maintains a studio space in Savannah, Georgia, and paints in Paris, France. Born in Mobile, Alabama, Hopkins grew up captivated by the Southern Antebellum Creole culture to which his family is intrinsically tied—a lineage tracing back to Nicolas Baudin, a Frenchman who received a Louisiana land grant in 1710. A self-taught artist and expert antiquarian, Hopkins channels his extensive knowledge of Creole material culture, architecture, and social history into paintings that are both historical documents and lyrical reimaginings. Visually, Hopkins’ compositions recall the folk traditions of Clementine Hunter, Grandma Moses, and Horace Pippin, yet his technical precision and layered storytelling distinguish his oeuvre. His works often depict the elegant interiors and street scenes of 1830s Creole port cities, rendered with exquisite attention to period details. In a radical departure from romanticized antebellum narratives, Hopkins introduces overtly homosocial or queer-coded elements, excavating the often-repressed histories of LGBTQ figures in the 19th-century South. His artistic practice is mirrored in his parallel persona as Désirée Joséphine Duplantier, a 1950s grande dame alter ego who embodies the theatrical, gender-fluid history of New Orleans. Hopkins’ work is internationally renowned, with features in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Garden & Gun, and Architectural Digest. His painting Self Portrait of the Artist as Désirée (2019) was acquired by the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., where the curator noted that it “significantly enhances our collection with its quality, rarity, and importance.” He recently concluded a year-long solo museum exhibition, Creole New Orleans Honey: The Art of Andrew LaMar Hopkins, at the Louisiana State Museum at the Cabildo in Jackson Square, accompanied by a dedicated publication of his work. On Hopkins’ rising influence in American art, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Jerry Saltz remarked: “People should see it.”

A Creole Family Mourning

14 x 11 inches

In this striking and meticulously composed tableau, Andrew LaMar Hopkins envisions a richly layered Creole mourning scene, infused with his characteristic devotion to ancestry, artifice, and opulence. At the composition’s heart stands a mourner draped in full mourning attire—her demeanor serene, her stature regal—positioned before a neoclassical tomb. She becomes both a tribute to the departed Jacques Louis Gabriel and a living embodiment of the drama and refinement of 18th-century New Orleans. The gravestone, inscribed with care and crowned by a veiled urn, evokes the sacred language of period funerary art.

True to form, Hopkins—an unrivaled stylist of historical reverie—fills the canvas with symbolic resonance: blooming tropical flora and ripe bananas native to Louisiana; a resplendent peacock hinting at beauty, pride, and theatricality; and, above it all, a ghostly gentleman whose gentle gaze from the clouds suggests remembrance, longing, and the eternal. Even within sorrow, joy emerges—seen in the graceful gestures, the contrast of black and white lace, and the lush energy of a banana tree stirring softly beside the grave.

Equal parts portrait and performance, this is Hopkins at his most evocative and exuberant. It is memory transfigured into myth, history rendered with vivid flourish, and mourning dressed in beauty, dignity, and devotion. Few contemporary painters approach the canvas with Hopkins’s blend of precision, pageantry, and a culturally resonant vision that is as reverent as it is resplendent.

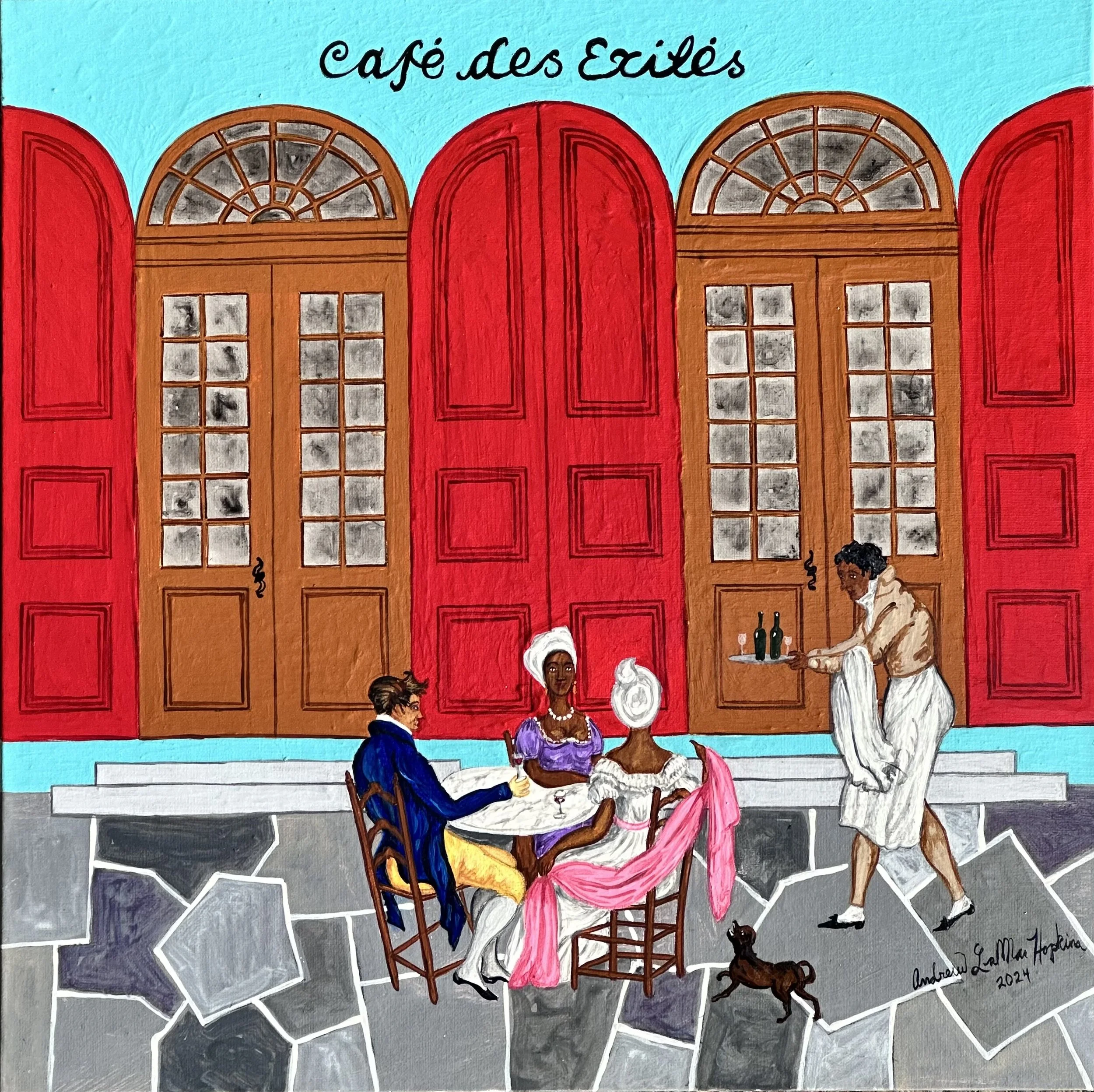

Café des Exilés

12 x 12 inches

This painting depicts Creole free people of color exiled from Haiti seated outside Café des Exilés”. In 1809, 9,000 people went to Louisiana from Haiti (it was close, people spoke French) — equal thirds white, free people of color, and slaves. This doubled the size of New Orleans. Café des Exilés was located on Rue Burgundy in the Old French Quarter. Opened by a Creole refugee from San Domingo. It was in an ancient Creole cottage sitting right down on the banquette, Creole word for sidewalk. The exiles from Haiti. Barbadoes, Martinique, San Domingo, and Cuba, sat their chairs out, sitting in their groups under the long, out-reaching eaves of the Creole cottage which shaded the banquette of the Rue Burgundy.

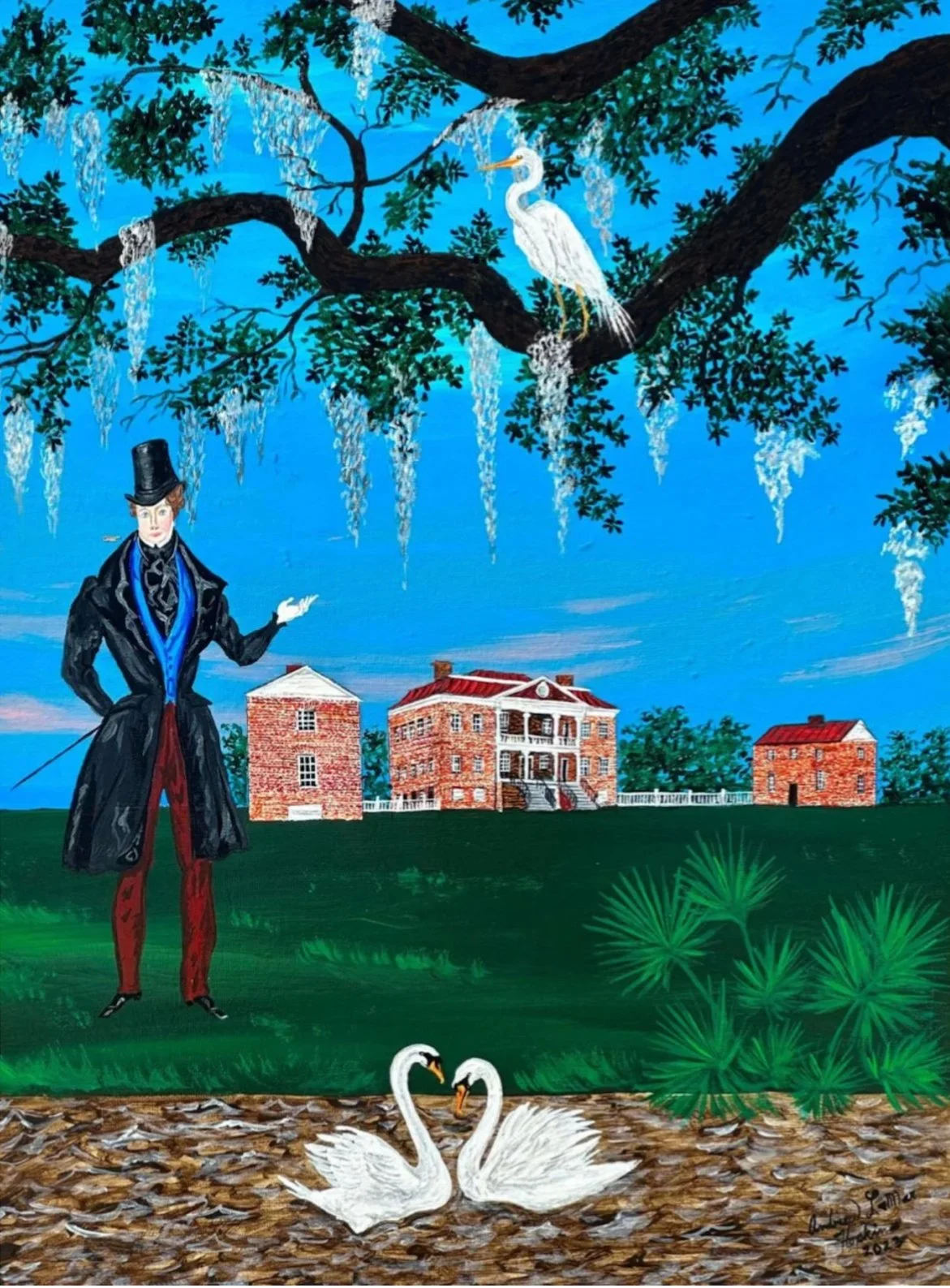

The Louisiana

Chinese Pagoda

16 x 12 inches

This painting depicts a Romantic Louisiana landscape with a beautiful Chinese pagoda tea house flanked by saucer magnolias and a free woman of color and a white creole gentleman. In front of the pagoda is a koi fountain with Chinoiseries polychrome lead fountain of a mandarin and dragon . Black and white Swans dot the landscape. The French have always had a passion for mixing Chinese/Chinoiseies decor, with traditional French design. And Louisiana Creoles were no different. 18th century Louisiana inventory list tapestries” with painted chinese figures, paintings with Chinese figures, Chinese lacquer furniture, Asian dressing glasses and trays, plus porcelain. In architecture country properties had garden Follies in the shape of Chinese Pagodas. Perhaps the best example of Chinese architecture in Antebellum Louisiana was a Chinese Pagoda built by Francois Gabriel Valcour Aime (1797-1867) at his famous plantation Le Petit Versailles. The Chinese pagoda Valcour built contained stained-glass windows and chiming bells. With grotto below the Pagoda!

Louisiana Creole Citrus Bod

14 x 11 inches

Part portrait, part pageant, this work is Hopkins at his most baroque and beloved. It is a scene of memory made mythic, history rendered in Technicolor, and freedom adorned—bare and beautiful. Few artists today wield paint like Hopkins does—with clarity, ceremony, and a sense of cultural reclamation that feels both radical and radiant.

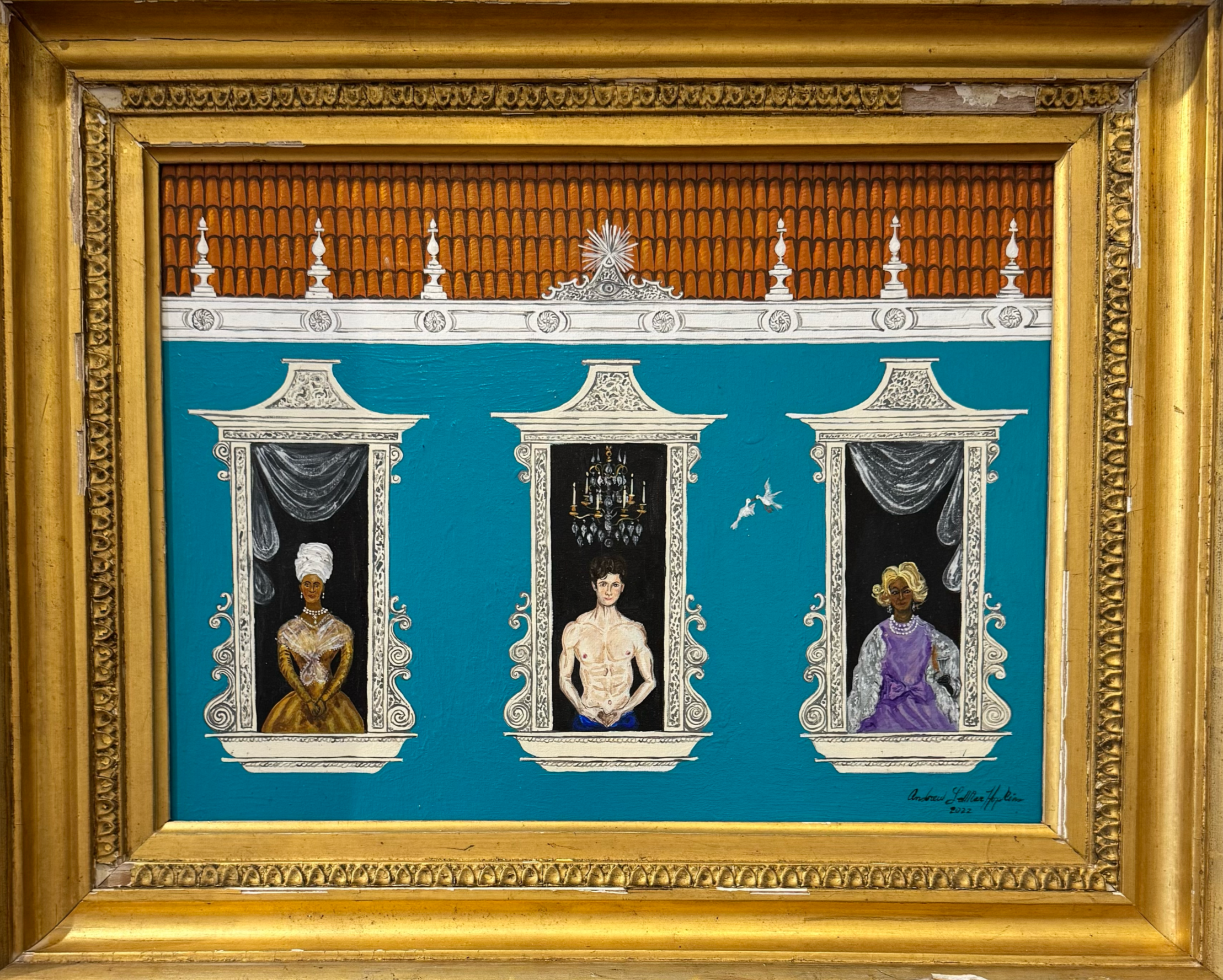

Secrets of the Creole Universe

12 x 16 inches

This painting portrays three elegantly framed Creole figures gazing from arched windows of an imagined French Quarter townhouse — a tableau blending fantasy and historical memory.

The central figure, shirtless and defiant, is flanked by two finely dressed women, one in a tignon and gold gown, the other in lavender lace and pearls — each representing the multiracial complexity and fluidity of Creole society in antebellum New Orleans. The architectural detailing draws inspiration from Spanish colonial ornamentation and 19th-century plaster work, with terracotta roof tiles and classical moldings evoking the grandeur of old Royal Street townhomes.

Set against a vivid turquoise backdrop, the painting becomes a symbolic balcony stage — a place where status, beauty, gender, and identity are displayed and contested. The birds mid-flight suggest transcendence, freedom, or perhaps the spirits of the past still circling the city’s wrought-iron windows. Hopkins, through his alter ego Mademoiselle de la Creole, presents a dreamlike but meticulously researched vision of a forgotten New Orleans — theatrical, queer, and unflinchingly Creole.

Introducing Artist in Spotlight—our new series celebrating the incredible artists of 812 Royal Gallery. First up for April: the legendary Andrew Hopkins. Known for his storytelling, generosity, and visionary work (recently featured in The New York Times), Andrew invites us into his creative world in a rare, intimate interview from late March.

Q: Your work reconstructs the largely erased histories of Free Creoles of color, particularly in New Orleans. Can you speak about why this history is so important to you, and how you approach bringing these stories to life in your art?

A: “The Gulf Coast narrative of free people of color is close and dear to my heart, firstly because it is a completely different narrative from that of enslaved people at the same time. Additionally, I have free people of color in my ancestry. Free people of color in New Orleans achieved great heights compared to others throughout the South due to the French and Spanish background of colonial Louisiana, which were more lenient on slaves and free blacks, as opposed to other places in the antebellum South. One-third of properties in the French Quarter were built, owned, or sold by free women of color prior to the Civil War. Free blacks were able to obtain great wealth through real estate transactions, as well as other businesses such as blacksmithing, building, hairdressing, street vending, and other businesses like tailoring, furniture making, silversmithing, goldsmithing, and carpentry. I bring these people’s stories back to life by honoring them in my art. Lots of research goes into it, such as census records. Knowing which properties and what people of color lived in these properties helps a lot, as well as death inventories. When a person died in Louisiana in the 19th century, everything in every room was documented in these inventories. They told us the types of furnishings, clothing, and decorative arts they would’ve had in their homes, as well as the value of the items. Whether they were newer or older items was usually documented in these inventories. Research like this gives us a better idea of how antebellum free people of color lived in Louisiana.” -Hopkins

Q: Can you share your background in antique dealing? Have antiques always fascinated you, and how does this interest influence your art?

A: “I have had an interest in antiques and old buildings since I was a small child. I grew up in a mid-century modern suburban neighborhood in Mobile, in a ranch-style house from the 1970s. The women in my family worked for wealthy white families, and we were given very nice antiques and hand-me-downs from these families that I grew up around. This was also mixed with more modern items, which I never really liked. Whenever we would go to downtown Mobile, I loved looking at the old buildings, so all of this transitioned into my art at a very early age. I became fascinated with antiques as well as old buildings, and re-creating them in my art as a child. When I got into my early teens, I began to explore Mobile, Alabama’s antique stores and became friends with many of the owners of these stores, who have now since passed away. I slowly began to collect various pieces of antiques that were damaged, but that I could afford at the time. By the time I was 20 and living in New Orleans with the help of my French boyfriend, I was able to open an antique store on Magazine Street and become an antique dealer. Throughout all this time, I was still creating art.” -Hopkins

Q: Can you speak to the importance of giving life to erased histories? How do you believe art has the power to shed light on the past?

A: “Not only do I paint the luxurious lifestyle of free people of color, but I also paint the forgotten people—people we take for granted. The people who washed clothes, the people who cooked food all day in a hot kitchen, and the people who beat the streets as street vendors in all kinds of weather to make a living. When you give these people a voice again and pay homage to what they have done, it brings about a sense of peace. Years ago, I got a commission from a friend who owned an 18th-century slave quarters/kitchen building in the French Quarter. She commissioned me to paint her interior, which depicted the kitchen and included a Creole woman cooking. When the painting was completed and hung in her home, she said the energy completely changed to peace.” -Hopkins

Q: Creole culture is known for its rich blend of traditions, languages, and history. How has your Creole heritage influenced your artistic style and the themes you explore in your work?

A: “I grew up eating gumbo, which was a dish made in the cooler winter months. I also grew up eating shrimp Creole. On Fridays, we did not eat meat; we ate seafood. As a small child, I remember going to the seafood market in Mobile with my grandmother to pick out fish, shrimp, and oysters, which were fried and eaten with potato salad and cooked vegetables. Creole is a culture, but it is also traditions passed down from generation to generation. My family’s history, as well as its culture, influences my art today. When you look at one of my kitchen paintings that shows women making gumbo or any other dish, you can see my connection to growing up on the Gulf Coast.” -Hopkins

Q: When beginning a new piece, which element comes first for you—historical research, the choice of color palette, or the incorporation of antique elements?

A: “I first see a painting in my head and then try to create it in the real world. As a historian and former French Quarter tour guide, I am quite familiar with New Orleans, Louisiana, as well as the Gulf Coast Creole history. I use the database stored in my head, along with books, documents, and photos in my archives, that might help with a painting. The first elements I focus on are the backgrounds. If it’s an interior scene, I start with the walls, floor, and ceiling, and then slowly add architectural elements, followed by people and furniture. If it’s a street scene, I start with the buildings in the background, sidewalks, and streets, and then begin to add local vegetation as well as people.” -Hopkins

Q: Your paintings often blend historical research with artistic reimaginings. How do you balance historical accuracy with creative interpretation in your work?

A: “From research, we pretty much know how free people of color lived in Louisiana, from the poor to the rich. But in doing so, I like to have fun as well, and I believe it gives my paintings a little personality by reimagining these interior and street scenes of old New Orleans.” -Hopkins

Q: Given your deep connection to Southern Antebellum Creole culture, how has your personal family history shaped your artistic journey? Are there specific memories or stories passed down through generations that you draw from in your work?

A: “I descend from free people of color on both my mother’s and father’s sides of the family in Mobile, Alabama, dating back to 1707. When a Frenchman named Nicholas Bodin immigrated to Mobile, he received a land grant from the King of France in 1710, upon which he started a plantation. By the 1730s, his household included mixed-race Black people of African and French descent. After Nicholas’s death in the 1740s, these mixed-race individuals were set free and given portions of his land grant. These free people of color were farmers who raised livestock and vegetables to sell in Mobile, Alabama, throughout the late 18th century and into the mid-19th century. They married into other free families of color in Louisiana and Alabama.” -Hopkins

Q: In your work, you introduce homosocial or queer-coded elements to challenge traditional antebellum narratives. Can you explain how you approach the depiction of LGBTQ histories, especially within the context of the 19th-century South?

A: “Gay people have always existed, even though it becomes harder to prove from this period. However, we know from census records that same-sex individuals who should have been married by a certain age chose to live together and set up households under the same roof without marrying. Does this mean everyone in these cases was gay? No, absolutely not. But in certain instances, the nicknames given and the social expectations of marriage by a certain age, combined with the choice not to marry, certainly suggest the possibility of same-sex relationships in antebellum Louisiana.” -Hopkins

Q: You maintain studios in both Savannah and Paris, and you’ve spent a significant amount of time in New Orleans. How do these cities and their respective cultural atmospheres influence your work differently, and do you find that your surroundings impact your creative process?

A: “I love very old cities that have flavor and soul. Walking the streets and looking at 200-year-old architecture, I like to imagine what street scenes, as well as the interiors of the old buildings, would have looked like during the periods I paint, which range from the late 18th century to the mid-19th century. Being in an old place gives me a lot of inspiration for my paintings.” -Hopkins

Q: Your alter ego, Désirée Joséphine Duplantier, plays a significant role in your artistic practice, embodying the gender-fluid history of New Orleans. How does this persona inform your work, and what role does it play in your exploration of identity and history?

A: “Désirée Joséphine Duplantier is a big part of my art, as well as my life and lifestyle. Désirée is a 1950s Creole lady who is sometimes depicted in my art. She represents a combination of all the strong-willed Black women I descend from and grew up around, some of whom are no longer here. Désirée also comes out in my fashion and cooking. I come from 300 years of Alabama cooking from Mobile. My grandmother, a strong-willed Black woman who raised me, taught me how to cook at the age of eight. So, when I cook my Southern delicacies and cuisine, I am paying homage not only to my grandmother and how I grew up but also to the 300 years of my ancestors living on the Gulf Coast, creating Creole dishes.” -Hopkins

Q: When beginning a new piece, which element comes first for you—historical research, the choice of color palette, or the incorporation of antique elements?

A: "I first see a painting in my head and then try to create it in the real world. As a historian and former French Quarter tour guide, I am quite familiar with New Orleans, Louisiana, and the Gulf Coast Creole history. I use the database stored in my head, as well as books, documents, and photos from my archives, to help with a painting. The first thing I work on is the background. If it’s an interior scene, I start with the walls, floor, and ceiling, then slowly add architectural elements, people, and furniture. If it’s a street scene, I start with the buildings in the background, sidewalks, and street, then begin to add local vegetation and people." -Hopkins

Marie Laveau

I hope you have enjoyed this interview with Andrew Hopkins. Please do not hesitate to reach out if you have any questions regarding his work or would like to see our inclusive price list paired with size, price, and historical context. Once again, I am incredibly proud to represent Andrew. Also if you would like to hear more from our artists, sign up for our Newsletter!

Kind Regards,

Kyla Isabel Bernberg